Dynamic Data Analysis – v5.12.01 - © KAPPA 1988-2017

Chapter

3 – P ressure Transient Analysis (PTA)- p82/743

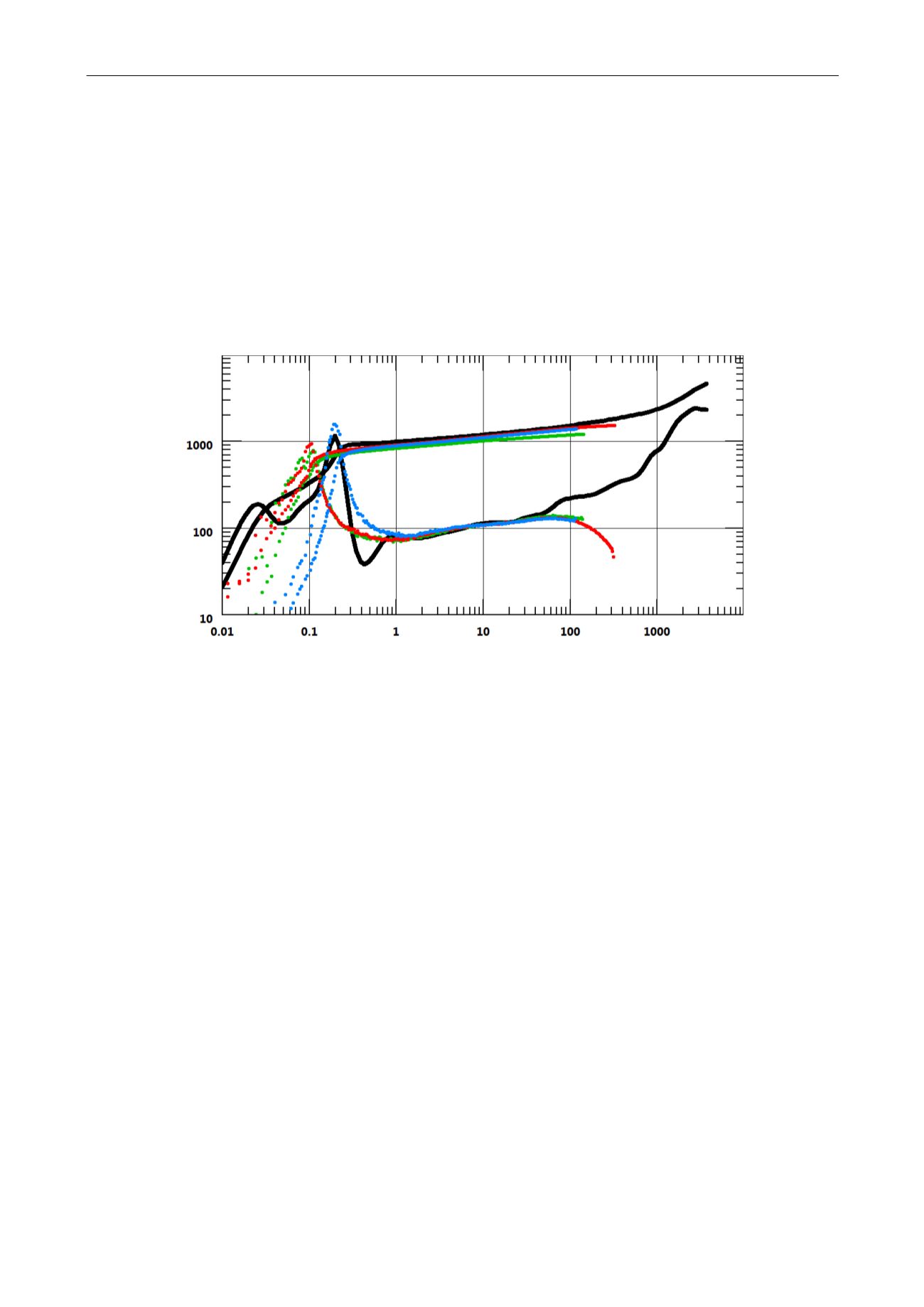

Any engineer that has been using nonlinear regression on analytical models knows how this

process is impressive when it succeeds and pathetic when it fails. It is the same here. The

inconsistencies at early time have forced the spline to oscillate to the best, actually least bad,

fit for the early time of the three build-ups. This had a residual effect at late time and the

spline had to oscillate again to get back on track. It is frustrating, because we do not really

care about the early time, and the late time of the three build-ups were telling more or less

the same thing. But the process has failed, because it is just a brainless numerical process that

is not able to incorporate this early / late time distinction. Hence, the process is doomed,

looking for a global solution that does not exist.

Fig. 3.D.14 – Deconvolution from the three BU’s

If we want to use deconvolution for, say, volumetrics from PDG data, we are likely to see the

wellbore storage and skin change over time. We face here a major potential limitation of the

deconvolution. It also kills any hope to have the deconvolution become a single button option

that would give the engineer a reliable late time response at no risk.

To be fair to the von Schroeter et al. method, it could give a more stable answer if we

increased the smoothing of the algorithm. This amounts to give more weight to the ‘minimum

curvature’ part of the error function at the expense of the ‘match data’ part. The algorithm

then sacrifices the accuracy of the match in order to get a simpler, smoother derivative curve.

The danger of using smoothing is to hide a failure of the optimization and get a good looking

but absolutely irrelevant deconvolution response. Such irrelevance could be detected when

comparing the reconvolved pressure response to the recorded data on a history plot. However

this problem is one of the main, frustrating shortcomings of the original von Schroeter et al.

method.

3.D.3

Deconvolution Method 2 (Levitan, 2005)

It is possible to perform a deconvolution for a single build-up if we combine the shut-in data

with a known value of initial pressure (see the consequences below in the paragraph ‘Pi

influence on the deconvolution’).

The workaround suggested by Levitan is to replace a single deconvolution for all build-ups by

one deconvolution for each build-ups.