Dynamic Data Analysis – v5.12.01 - © KAPPA 1988-2017

Chapter

3 – P ressure Transient Analysis (PTA)- p76/743

3.D

The use of modern deconvolution

Deconvolution in Pressure Transient Analysis has been the subject of numerous publications.

Deconvolution could tentatively be used (1) to remove wellbore storage effects in order to get

to IARF earlier, (2) to turn a complex noisy production history into an ideal drawdown ready

for interpretation, (3) to explore boundaries not detected by individual build-ups.

Despite the good hard work done on the subject, true deconvolution is fundamentally unstable.

To add stability into the deconvolution process one has to make assumptions that bias the

response. Until recently, when a new paper was published on the subject, the natural question

would not be “does it work?” but rather “where’s the trick?”.

This is no longer the case. A set of publications, initiated by Imperial College and

complemented by bp (e.g. SPE #77688 and SPE #84290), offer a method that actually works,

especially, although not exclusively, to identify boundaries from a series of consecutive build-

ups. There is a trick, and there are caveats, but the trick is acceptable and the method can be

a useful complement to PTA methodology.

Saphir offered on October 2006 the first commercially available version of this method. It was

since improved by adding additional methods and it is now a totally recognized and helpful

method, able to provide additional information, unseen through other techniques.

3.D.1

What is deconvolution? Why do we need it?

3.D.1.a

The need

Analytical models are developed assuming a perfectly constant production as drawdown type-

curves. In reality a well test, or a well production, is anything but constant. Rates vary in time,

and the producing responses are generally so noisy that we usually focus on shut-in periods

only.

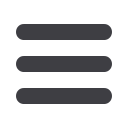

In the simulated example shown on the plot below, the total production history is 3,200 hours,

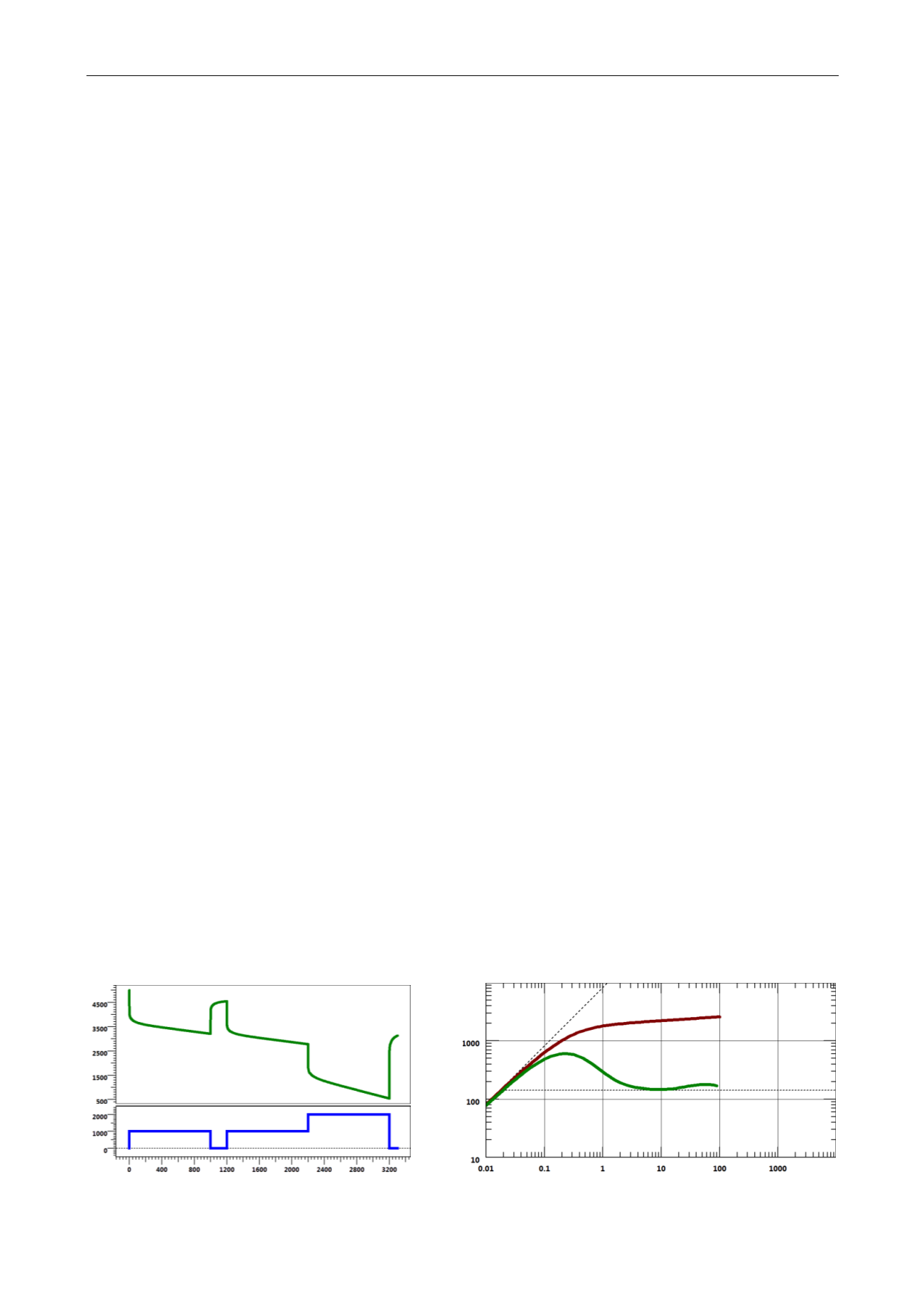

and the build-up is only 100 hours long. What we see on the loglog plot corresponds to only

100 hours of diffusion. We use the superposition of the rate history in the derivative

calculation, but this is only to correct superposition effects; we really only see 100 hours of

diffusion.

But there is more than 100 hours of information in the total response. Pressure has been

diffusing for 3,200 hours, some locations far beyond the radius of 100 hours of investigation

have felt the effect of the production and this information has bounced back to the well. So

there is more information somewhere in the data, but not in the build-up alone.

Fig. 3.D.1 – History:

p

w

(t) & rates

Fig. 3.D.2 – Build-up:

p

w

(t) &

p’

w

(t)